The entertainment industry is oversaturated with blood, fangs and garlic cloves. Vampirism has always been a popular theme in Hollywood, the 90s giving us “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” and Anne Rice’s Interview with a Vampire. With the resurging popularity of the Twilight book series and film adaptations and HBO’s “True Blood”, it’s now time to see how foreign film markets shed new light on this popularized and nearly over exposed story.

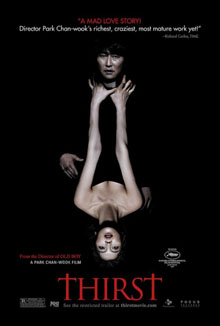

Thirst marks the return of Korean director Chan-wook Park, who is well known for his “Vengeance Trilogy” which includes the critically acclaimed, Oldboy. His films are notorious for their graphic yet inventive violence and sexuality and also their complex plots. Thirst is no different. The film begins with the story of Priest Sang-hyeon, played by Park recurrent Kang-ho Song, who after a failed medical experiment testing a new vaccine for a deadly virus, is brought back to life as a vampire after a transfusion of contaminated blood. While trying to return to his everyday life as a priest, Sang-hyeon struggles with his identity as a priest and also as a vampire as his extreme thirst for human blood and his other carnal desires, instigated by his childhood friend’s wife, Tae-joo, played by Korean newcomer Ok-vin Kim, threaten to keep him from his wish to help heal the sick and save people from themselves.

The film is a more complex adaptation of the vampire film, focusing more on the internal battles and philosophic ideals of the characters than on the stereotypes associated with vampires. Though these vampires do have super strength, super speed and the ability to leap small buildings in a single bound, these abilities are understated and not kosher. So instead of sparkling in the sun like super bedazzled handbags (sorry Twi-hards), the sun turns them to burning ash.

Each character in the film is strongly developed and their actions are believable. Kang-ho Song gives a strong performance as the lead, completely enveloped in his character’s moral agony and paradox. He is able to effectively show this outwardly when making decisions that range from changing his close friends into vampires to drinking the blood of patients at the hospital he visits regularly. For the actress’s fifth feature film, Ok-vin Kim is conniving and eerie as she transforms smoothly from a calm yet closeted neurotic wife who’s sick of her bland life to a full-fledged evil vampire, thirsty for nothing but the best fresh flowing blood.

The cinematography and look of the film is spot on, as Park begins the film with neutrals and muted tones, a stark canvas meant to accentuate all the blood red, the film’s only warm tone. This is brilliantly displayed when Sang-heong is sitting at his desk in his hospital room attempting to play a song on his white recorder, when suddenly the blood begins to spew out his nose and mouth like water, running viciously through his recorder like a fountain. As the film goes on we see more vibrant colors begin to come in through the actor’s clothing and the set decoration (a signature of Park’s), but these are all cool tones, staying mostly within the blues and purples. After her transformation into a vampire, Tae joo almost exclusively wears royal blue complimented only by white and other neutrals throughout the rest of the film.

The editing style is bold, taking modern style and combining it with eye-catching shots and camera work to create extreme suspense. The audience is able to do nothing but squirm as the camera closes in on Tae joo, who begins move a pair of what looks like cuticle scissors in a stabbing motion into her husband’s open mouth while he sleeps, the camera following every stabbing motion, up and down, until it cuts away to the next scene. The editing is also complex. Park does not spoon-feed the story to the audience, expecting them to figure out minor details for themselves through what’s given.

Park creates suspense through his soundtrack as well. Park’s films usually have beautiful concoctions of music that help express the story through more than just the plot and characters, but what’s surprising in Thirst is the lack of soundtrack. He uses the silence in this film to emphasize what sounds there are, like the music of Sang-heong’s recorder or the blip of the heart monitor at the hospital that is transformed into light music. But the silence is what adds to the eerie context of the film.

Though the intense violence and sexual situations might keep some viewers from watching, the intention is for a realistic twist to the vampire legend not found in the blatantly over sexed woods of “True Blood” or on the shiny skins of Twilight. Park doesn’t sugar coat a thing and tries to bring a tired genre back to its roots, with a twist. The result is a mind-blowing experience that will leave you a little disturbed, something that Park wishes for all of us.