|

l From the Publishing History column of the May 2002

Perspectives

Editor's Note: This is a revised version of an article first published in the May 2002 issue of Perspectives [link to original]. It seems we have arrived at a point of general agreement that historical scholarship can be published online without losing its integrity or quality. But doing serious history online takes more effort and work than history that goes from the word processor to the printed page, so the possibilities of the online medium will remain stifled until we develop the institutional support and incentives to do it properly. [1] Insofar as tenure and promotion remain tied to the production of articles and monographs, it seems vitally important to assess how online publication can extend history scholarship in new directions, while maintaining its integrity as good scholarship. To facilitate a new understanding, we need to do a better job of differentiating the types of scholarship on the web—and the function and value of each—to both sketch out what is possible and lay a groundwork for incorporating this form of scholarship into the academic reward system. The lack of clear conceptual vocabulary makes new work in the medium difficult to describe and define. These works can range from straightforward reproductions of a printed text to technically sophisticated web productions encompassing hundreds of pages of text and supporting multimedia. So discussing even the most basic issues of concept, cost, and reward in the production of new types of history can quickly become quite confused. As a starting point, I encourage authors and faculty to imagine online scholarship as existing on a continuum marked by three principal categories or ideal types:

Each type points toward specific problems and opportunities in the medium, and forces us to differentiate the way we think about the scholarship that is now appearing in digital form. Text-based Scholarship

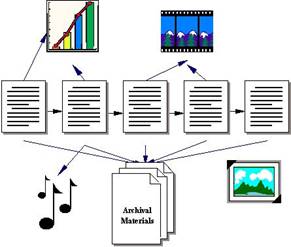

Much of what we think of as online scholarship today is text-based, consisting of materials in print as articles, monographs, or books that the publishers converted to electronic form for display and distribution on the web (Figure 1). This material offers no hot links and no icons promising a soundbite, music, or a snippet of video. While this material is not transformed by or for the medium, it does take on an added functional value by becoming part of a vast database of knowledge. It may be freely accessible to anyone with a web browser and the ability to use the Google search engine, or it may be partially concealed behind the barriers of a proprietary database. In either context, this vastly increases the potential audience for a specific work—something most authors readily appreciate—and provides potential readers with wider and more immediate access to some of the best history being produced today. Readers with a substantive (but not necessarily academic) interest in history can immerse themselves in some the best and latest scholarship in the discipline, and no longer have to wait years for developments in the historiography of a particular subject to be integrated into textbooks and the secondary literature. And few scholars can resist the added value of keyword searching through the materials on J-STOR and the History Cooperative. The growing legitimacy of this online material demonstrates that articles and monographs can make the shift to online publication without being fundamentally compromised. More important for present purposes, these publications serve as a baseline for assessing various other forms of scholarship that have begun to appear online. If scholarship is not degraded by such straightforward electronic publication, it is not greatly enhanced either. Supplemented Scholarship

While text-based scholarship is growing in popularity and use in the field, this is not what proponents of the medium have in mind when they talk about its potential. Typically they look to and describe supplemented texts. These works make greater use of electronic enhancements than the simple text-based scholarship, which usually consist either of external links—to materials somewhere else on the Internet—or internal links that take the reader into a deeper archive of primary documents and materials assembled by the author(s). These kinds of links create an added layer of depth—providing more immediacy to the footnotes and allowing the reader to engage in the larger argument and evidence. Supplementation can take multiple forms, as supplemental materials can consist of direct evidence for points in an essay or book; they can provide multimedia illustrations that cannot be done in print; or they can serve as electronic appendices, providing an essentially archival function. One of the best examples of the archival aspects of supplemented scholarship can be found in Robert Darnton’s “An Early Information Society: News and the Media in Eighteenth-Century Paris.” A number of multimedia components of this article—an interactive map and audio versions of 18th century French songs—significantly enliven and enrich the text, offering the reader a much wider range of contexts for their reading. Moreover, the use of the medium allows for an added range of sensory ways to experience the text. However, while such material can expand one’s reading of the text, a crucial distance remains between the article and the supplementary materials. The most interesting supplements are referred to only in passing in the text. This largely leaves it to the reader to decide how much or how little of the supplementary material to delve into, as the author never directs the reader to take a moment to view an aspect of the map, or listen to one of the songs.

Some recent publications in the Journal of Multimedia History demonstrate the same illustrative use of multimedia and images. While they serve to enliven the articles and offer some additional materials for the readers' consideration, these multimedia elements are not integrated into the interpretive apparatus of the articles. The materials are connected to the articles largely through the captions or other text external to the scholarly argument contained in the body. For instance, Gerald Butters's essay "From Homestead to Lynch Mob: Portrayals of Black Masculinity in Oscar Micheaux's Within Our Gates," provides a number of movie clips which are a crucial element in his analysis, but he creates an interpretive argument that does not rely on the reader looking at the clips. Where he does a close reading of successive scenes, he feels compelled to provide a textual description of the crucial elements he has in mind—note for instance the sequential list of scenes in part 2. As a result, looking at the movie clip becomes optional and extraneous from the argument. This is certainly not to imply that these articles are any less valuable as scholarship, only that the medium has not fundamentally changed the message. Nevertheless, credit has to be given to authors who have taken on the added burden of including these supplementary materials. They have created a new archive of primary source material that other scholars can draw upon to make new versions of online supplemented scholarship. At the same time, the text is more open than a standard journal article, as readers can immediately do a bit of fact checking on the author and draw a few conclusions of their own. The materials in these supplemented articles and monographs need to be judged on separate criteria. The supplemental materials have to be evaluated as a collection of primary sources—assessed for their accuracy and quality of presentation—while the scholarship in the article or monograph has to be judged by the quality of the interpretive argument and the mustering of facts. As peer review is extended to online versions of journal articles and monographs, the reward system of the academy needs to give both components their due as serious and substantive contributions to the field.

Reconceptualized Scholarship

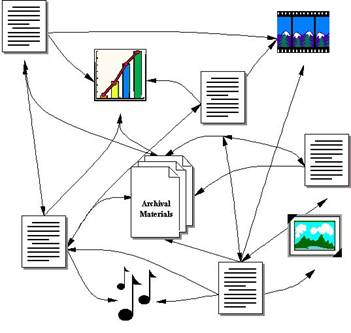

Further along the continuum from text-based scholarship, a growing number of scholars envision new forms of scholarship that reimagine the article or monograph from the ground up.[2] There is a small but growing number of examples of historians trying to transcend scholarship that can fir on a printed page. Philip J. Ethington’s “Los Angeles and the Problem of Urban Historical Knowledge” points us in this direction. Ethington envisions a “web site—composed of images (still, panoramic, moving, and sequential), maps, short essays (epistemological, bibliographic, methodological, and conceptual)—[that] is written as a totality; the verbal text and other media are meant to be encountered as a whole.” Ethington’s article is conceptualized from the ground up to take full advantage of the medium, weaving together the narrative and the primary documents in the site. At a number of points in the article, Ethington directs the reader to view a particular group of images with specific interpretive guidance. Note for instance the interpretive discussion around different historical images of Broadway (just after footnote 11). The reader is guided through the images, not simply pointed in the general direction of some supplemental materials. Other works, like David Westbrook’s “From Hogan’s Alley to Coconino County: Four Narratives of the Early Comic Strip,” try to weave together multiple readings and narratives into single article. As he observes the layering and interactivity afforded by the medium allowed him “to represent more accurately the nature of the relationships among these theses and the primary materials they attempt to describe.” Obviously, any attempt to describe the current state of play has to be provisional. But even this very loose range of types points toward some of the fundamental questions opened by online scholarship. At the most basic level, trying to reconceptualize scholarship for the medium challenges entrenched notions about what history scholarship is and should be. At a more mundane level, constructing scholarship that aims toward the side of full reconceptualization for the medium inevitably ratchets up the costs, imposing added burdens for authors, editors, collaborators, and the readers who need to learn new ways of reading such materials. As new authors present new examples to the field, the spectrum will undoubtedly differentiate itself into additional subtypes. For instance, one can easily imagine, a more detailed taxonomy of reconceptualized scholarship, in which we classify the publications by the predominant type of media they incorporate into their work. For the moment it should suffice to note that history scholarship can make a more substantive use of the Internet. The profession now has to decide whether and how we will credit and reward such work in the future.Robert B. Townsend is assistant director for publications, information systems, and research at the American Historical Association. Special thanks to Roy Rosenzweig, Michael Grossberg, William Thomas, and Frances Clarke for their insightful readings and suggestions.

Notes[1] See Robert B. Townsend, " Lessons Learned: Five Years in Cyberspace ," Perspectives (May 2001), 3; Anthony Watkinson, “Electronic Solutions to the Problems of Monograph Publishing,” The Council for Museums, Archives and Libraries, 2001, 36-8 and Jennifer M. Siler, “From Gutenberg to Gateway: Electronic Publishing at University Presses,” Journal of Scholarly Publishing 32:1 (October 2000), 9–23. [2] See for instance George P. Landow, Hypertext 2.0: The Convergence of Contemporary Critical Theory and Technology (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1997); Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin, Remediation: Understanding New Media (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1999); and Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2001). Copyright © 2002 by American Historical

Association.

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||