An Uncommon Afterlife:

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

By KATIE WALKER

Glance at any grocery store checkout stand and you’ll see dozens of gossip magazines extolling the virtues of the latest anti-aging serum. Turn on the news and you’ll find celebrities touting the newest cosmetic procedures to bend the laws of time and gravity. In a culture so immersed in the pursuit of immortality, Henrietta Lacks’ anonymity is ironic.

Henrietta Lacks was the first person to achieve eternal life. To be more specific, her cells—cancer cells, the sample taken without her permission just days before her death in 1951—never died. While most cells die within hours of extraction, Henrietta’s virulent strain of cervical cancer cells have been multiplying in laboratories around the globe for over half a century. The immortal cell line has helped spawn an era of genetic engineering and played a key role in numerous of medical discoveries, including the invention of the polio vaccine, modern chemotherapy, and animal cloning.

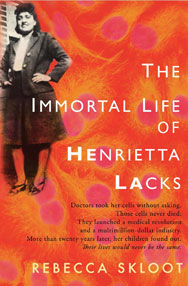

Henrietta leads an uncommon afterlife, but her earthly existence seems devastatingly unremarkable in comparison: the granddaughter of slaves, she worked as a tobacco farmer in the sharecropping town of Clover, Virginia. And while an ewe named Dolly, the first cloned animal, has been immortalized in every middle school science textbook printed since 1999, no photograph accompanies the abbreviation “HeLa”commonly used to denote Lacks’s cell line in scientific literature. In fact, only one image of Henrietta exists. In the grainy black-and-white snapshot that graces the cover of The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, she smiles broadly with hands on her hips; it’s the kind of photo meant to show off a stylish outfit, not a portrait befitting a scientific icon.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks is, on its surface, a biography of Henrietta as unlikely scientific heroine, but Rebecca Skloot’s first book transcends the expectations of traditional biography. An experienced scientific journalist, Skloot investigates the ethical ramifications of Lacks’s unintentional contribution to medicine with remarkable clarity and passion. She recounts not one life but two, intertwining the stories of HeLathe cell and Henrietta the woman with journalistic sophistication and poetic elegance.

Through an innovative story framing device, Henrietta’s descendants become characters in her story; chapters alternate between Skloot’s personal experiences with the modern-day Lacks family, stories of HeLa’s profound effect on medicine, and the events immediately surrounding Lacks’s life and death. In the context of her interviews and research, Skloot herself becomes a character in the contemporary narrative, establishing an even greater degree of intimacy with the reader. While I found the lack of chronological order jarring at first, this style aids the author’s seamless transitions between Henrietta’s hometown and the ivory-tower realm of scientific research.

Skloot demonstrates an immense talent for crafting three-dimensional characters. In her hands, even HeLatakes on a personality of its own. When Skloot describes her visit to observe HeLacells at a Johns Hopkins laboratory, it sounds more like a journey to Mount Olympus than an academic venture; Skloot envisions immortal Henrietta enshrined as a goddess. Without a trace of condescension, the author manages to populate Lacks’s impoverished neighborhood and cutting-edge scientific research facilities with equally believable characters. She doesn’t merely create believable dialogue out of respect for their experiences, she delivers the voices of the Lacks family unedited using phonetic spelling to emulate their spoken dialects.

Skloot’s decision to incorporate her interactions with the modern-day Lackses transforms this biography into a contemporary dialogue at the intersection of medicine and ethics. From the Lackses’ perspective, doctors took Henrietta’s cells without her consent, without a word of gratitude, and continue to profit from their theft; moreover, despite Henrietta’s unrivaled contributions to science, several family members can’t afford health insurance. Throughout the narrative, Skloot returns to the question: what makes our bodies our own? Where do the individual’s rights end and the doctor’s begin?

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks refuses to be shelved neatly into the category of medical journalism, ethics, or human interest story, though it works on each of these levels. In the context of Henrietta’s life and death, Skloot explores the borderlands between science and imagination. Rebecca Skloot’s masterfully executed debut reads like the kind of novel you can’t abandon long enough to wolf down breakfast (lunch, or dinner)—the kind whose lucid prose will linger in your memory long after you close its cover.